The gift of a telescope as a young child sparked a deep and lasting interest and love in me for the sky above and for scientific exploration. They led to the choice of a career in aviation, first studying aeronautical systems engineering and management, then becoming an airline pilot with the further intention of becoming an astronaut. The aurora borealis is one of the things I enjoy seeing most from the cockpit. I actively request flights to the US west coast to get a chance of seeing the northern lights on the homebound night flights, calling colleagues from the cabin into the cockpit when we see the green awesome sauce, as astronaut Jack Fisher once called the undulating curtains of light.

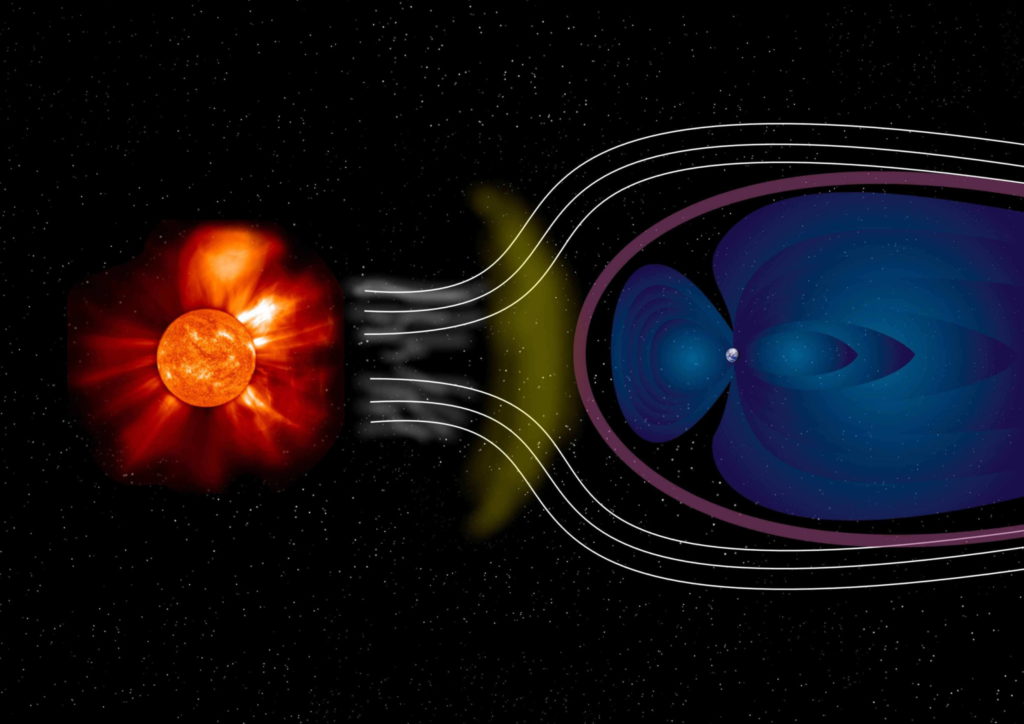

150 million kilometers away, the 4.6 billion-year-old ball of plasma we know as the Sun is essential to life on Earth. Its light keeps us warm and lets us see. But there’s more coming from the Sun than what we can detect with our senses. The solar wind, a constant stream of electrons, protons and atomic particles, fills the seemingly empty space in our solar system. Earth’s magnetosphere protects us from this “wind”, deflecting charged particles along its field lines to the poles, where they light up the sky as the aurora. Once in a while, explosions on the Sun create coronal mass ejections (CMEs) many times more powerful than the solar wind, disturbing Earth’s magnetic field and causing geomagnetic storms. Most pilots know that this influx of particles can be a health hazard to crew and passengers, disturb HF radio communication as well as induce currents in power grids, possibly crippling ground stations required for navigation and air traffic control. But few realize that even the accuracy of GPS, a system we have come to rely on heavily and trust nearly blindly, can be severely degraded.

Image: ESA

Only recently, what we know as “space weather” has found a place in an ICAO document delineating its effects on communication, navigation, surveillance radar and radiation protection. While the International Civil Aviation Organization has acknowledged the existence and magnitude of this danger, the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) neither mentions it in its regulations, nor has it followed the recommendation of the European Cockpit Association (ECA) to integrate space weather into its training syllabus (Sievers, VC Info 1/2019).

In January 2019, the European Space Agency invited interested applicants to the #AuroraHunters SocialSpace event. Its idea is to bring together people from all walks of life interested in space weather and ESA’s role in improving Europe’s ability to detect and predict space weather, protecting our civilization from its effects on satellites and ground infrastructure. The star-studded program promises participants the chance to meet and interact with ESA and European space weather scientists; receive briefings and updates on solar physics, space weather, aurora borealis, space technology and current developments in Europe’s space weather warning missions and services; learn about ESA’s space safety and security activities; visit the world-famous Tromsø Geophysical Observatory; even join a wildlife-viewing boat cruise and a guided aurora hunting expedition.

I feel honored and excited to receive a spot in this group of 30 lucky people flying to Tromsø in Northern Norway from March 3-5. With the organizers and speakers, we are a quirky mix of unique individuals from 13 countries and 17 nationalities: scientists, engineers, teachers, journalists, writers, photographers, even a lawyer and this airline pilot. After receiving our invitations, we quickly mingle online and not only share tips for cold-weather clothing and aurora photography, but also bounce around ideas for regional specialties to bring from our respective countries and share with the others. It’s an open-mindedness that I have rarely seen, even in a career full of international travel.

To make the most of the journey to the far north, I fly to Tromsø one day earlier and extend my stay to a full week, booking a rental car and an Airbnb to explore more of Northern Norway after the ESA event. The weather in the days leading up to the event is nasty, but on the day of my flight, it’s the best it can be. I’m flying on a staff travel ticket and get to experience the challenging RNAV circling approach through the fjords from the observer seat of the A319 cockpit. The terrain around TOS quickly rises to over 3000′ on all sides, even 4000′ to the south and east. While there is an instrument landing system for approaches from the north, it is common to fly the ILS from the south followed by the circling to runway 19 during southerly winds. The approach follows a 4° glide path (1° more than the norm) to a position five miles south of TOS. There, it breaks off to the northeast, following the fjord with sensational views of the city at an altitude of just over 2000 feet before circling around Tromsøya island to land on the runway on its west coast.

I’m not the only early arrival. One of the teachers, an American living and working in Germany, is on the plane with me and we make our way to the city just a few kilometers from the airport. With a population of 71,000, Tromsø has a very well organized public transportation system utilizing two apps – one with a timetable and live tracking of buses, the other for buying online tickets. Once we reach the city center, Nancy and I split up to get settled in our accommodations. For the first night, I’m in an Airbnb overlooking Tromsø and Tromsdalstinden mountain on the other side of the fjord. What it lacks in comfort, it makes up for in views – maybe even of the aurora tonight! After changing into some warmer clothes – the temperature is well below freezing, an icy cold wind giving it that extra edge – I walk back to the city center to explore.

As I always do when I fly to new places, I’ve researched where to go and what to see ahead of time and used Google MyMaps to visualize it. A couple of other early arrivals follow my lead to the places I have decreed every tourist needs to go to (yes, I have a definitive partiality for the culinary): drink coffee and eat pastries at Kaffebønna, have a burger at the student-run Driv and drink beer at the world’s northernmost brewery. (Mack actually no longer holds this title since a brewery opened in Svalbard, but it still sounds bucket-list-worthy and awesome!) It amazes me how a heterogeneous group of people who have just met interacts as if we’ve known each other for a much longer time. That common burning for science, knowledge, and exploration binds us together in a way very reminiscent to the coolest airline crews with which I’ve had the joy of spending layovers around the world.

By the time we enjoy our burger, it’s already dark outside and the aurora hunters are itching to see some of that magical light in the sky. And indeed, fighting hard against the light pollution of Tromsø, a delicate green arch spans nearly motionless across the sky. Leaving Mack’s Ølhallen with its excellent beer and sobering prices – expect to pay the equivalent of 10 € or more for a scant pint – a part of the group heads to Telegrafbukta, hoping to get a clearer and less light-polluted view of the aurora. My Airbnb is in the opposite direction, so we part ways for the night. On the walk back to my apartment, the ionospheric light show starts heating up. Every few minutes, I have to stop to take pictures as it waxes and wanes overhead. I reach the Airbnb, step out onto the balcony and watch in awe as the sky explodes with colorful light. For only a minute, the most brilliant and active aurora I have ever seen rains down on Tromsø, only to stop as quickly as it started.

Since the building I am staying in was blocking significant parts of the display, I head out again in search of an open space with less light pollution. I find a beautiful snow-covered park with an extensive network of groomed cross-country skiing tracks, but it is lit up bright as day – understandable in a place that does not see the Sun for two whole months in the winter, but still disappointing. Walking on, I finally discover a great photographic foreground and a preview of one of the upcoming field trips: the parabolic antennas of KSAT satellite station. I manage to snap a few pictures of the aurora over the largest dish, but there is no encore to the evening’s most brilliant display. I decide to call it a night, head back to the Airbnb and go to bed, reliving a fantastic day as I drift into the land of dreams. So much more lies ahead of me, as tomorrow marks the official start of the AuroraHunters event. Read about it in Part 2, coming soon!

Hi! Must been a wonderful experience for you, Ulrich Beinert! Great images! Cheers, Lis

Hi Lis, it was wonderful. I have yet to write the second part, the one about the official event! So much to do, so little time… Regards, Ulrich